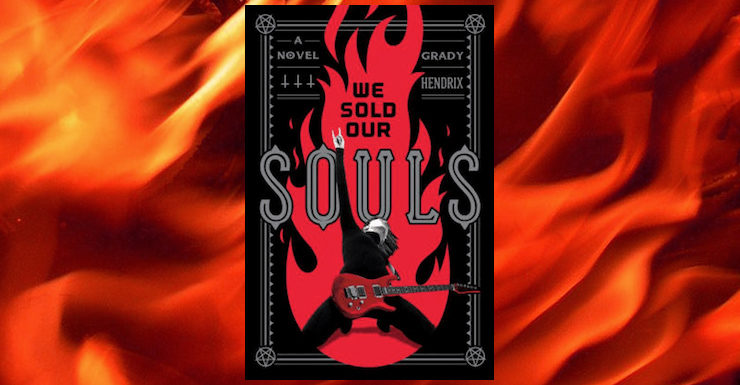

In the 1990s, heavy metal band Dürt Würk was poised for breakout success—but then lead singer Terry Hunt embarked on a solo career and rocketed to stardom as Koffin, leaving his fellow bandmates to rot in obscurity.

Two decades later, former guitarist Kris Pulaski works as the night manager of a Best Western—she’s tired, broke, and unhappy. Everything changes when a shocking act of violence turns her life upside down, and she begins to suspect that Terry sabotaged more than just the band.

Kris hits the road, hoping to reunite with the rest of her bandmates and confront the man who ruined her life. It’s a journey that will take her from the Pennsylvania rust belt to a celebrity rehab center to a music festival from hell. A furious power ballad about never giving up, even in the face of overwhelming odds, Grady Hendrix’s We Sold Our Souls is an epic journey into the heart of a conspiracy-crazed, pill-popping, paranoid country that seems to have lost its very soul… where only a lone girl with a guitar can save us all. Available September 18th from Quirk Books.

True as Steel

Kris sat in the basement, hunched over her guitar, trying to play the beginning of Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man.” Her mom had signed her up for guitar lessons with a guy her dad knew from the plant, but after six weeks of playing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” on a J.C. Penney acoustic, Kris wanted to scream. So she hid in the park when she was supposed to be at Mr. McNutt’s, pocketed the $50 fee for the two lessons she skipped, combined it with all her savings, and bought a scratched-to-hell Fender Musicmaster and a busted-out Radio Shack amp from Goldie Pawn for $160. Then she told her mom that McNutt had tried to watch her pee, so now instead of going to lessons Kris huddled in the freezing cold basement, failing to play power chords.

Buy the Book

We Sold Our Souls

Her wrists were bony and weak. The E, B, and G strings sliced her fingertips open. The Musicmaster bruised her ribs where she leaned over it. She wrapped a claw around the guitar’s neck and pressed her sore index finger on A, her third finger on D, her fourth finger on G, raked her pick down the strings, and suddenly the same sound came out of her amp that had come out of Tony Iommi’s amp. The same chord 100,000 people heard in Philly was right there in the basement with her.

She played the chord again. It was the only bright thing in the dingy basement with its single 40-watt bulb and dirty windows. If Kris could play enough of these, in the right order, without stopping, she could block out everything: the dirty snow that never melted, closets full of secondhand clothes, overheated classrooms at Independence High, mind-numbing lectures about the Continental Congress and ladylike behavior and the dangers of running with the wrong crowd and what x equals and how to find for y and what the third person plural for cantar is and what Holden Caulfield’s baseball glove symbolizes and what the whale symbolizes and what the green light symbolizes and what everything in the world symbolizes, because apparently nothing is what it seems, and everything is a trick.

This was too hard. Counting frets, learning the order of the strings, trying to remember which fingers went on which strings in which order, looking from her notebook to the fretboard to her hand, every chord taking an hour to play. Joan Jett didn’t look at her fingers once when she played “Do You Wanna Touch Me.” Tony Iommi watched his hands, but they were moving so fast they were liquid, nothing like Kris’s arthritic start-and-stop. It made her skin itch, it made her face cramp, it made her want to bash her guitar to pieces on the floor.

The basement was refrigerator cold. She could see her breath. Her hands were cramped into claws. Cold radiated up from the concrete floor and turned the blood inside her feet to slush. Her lower back was stuffed with sand.

She couldn’t do this.

Water gurgled through the pipes as her mom washed dishes upstairs, while her dad’s voice sifted down through the floorboards reciting an endless list of complaints. Wild muffled thumps shook dust from the ceiling as her brothers rolled off the couch, punching each other over what to watch on TV. From the kitchen, her dad yelled, “Don’t make me come in there!” The house was a big black mountain, pressing down on Kris, forcing her head into the dirt.

Kris put her fingers on the second fret, strummed, and while the string was still vibrating, before she could think, Kris slid her hand down to the fifth fret, flicked the strings twice, then instantly slid her hand to the seventh fret and strummed it twice, and she wasn’t stopping, her wrist ached but she dragged it down to ten, then twelve, racing to keep up with the riff she heard inside her head, the riff she’d listened to on Sabbath’s second album over and over again, the riff she played in her head as she walked to McNutt’s, as she sat in algebra class, as she lay in bed at night. The riff that said they all underestimated her, they didn’t know what she had inside, they didn’t know that she could destroy them all.

And suddenly, for one moment, “Iron Man” was in the basement. She’d played it to an audience of no one, but it had sounded exactly the same as it did on the album. The music vibrated in every atom of her being. You could cut her open and look at her through a microscope and Kris Pulaski would be “Iron Man” all the way down to her DNA.

Her left wrist throbbed, her fingertips were raw, her back hurt, the tips of her hair were frozen, and her mom never smiled, and once a week her dad searched her room, and her older brother said he was dropping out of college to join the army, and her little brother stole her underwear when she didn’t lock her bedroom door, and this was too hard, and everyone was going to laugh at her.

But she could do this.

…

34 Years Later

Frozen in the right-hand lane of US-22, Kris stared up at what loomed on the horizon and felt her spit turn thin and bitter. Her breath got fast and high in her chest as she witnessed the hideous thing rising over Gurner, sprung up overnight like some dark tower from The Lord of the Rings.

The Blind King was back, staring down at her from the massive billboard with his black, pupil-less eyes. In Gothic font, the billboard read:

KOFFIN — BACK FROM THE GRAVE

Beneath it was a photo of the Blind King. A brutal spiked crown was nailed to his head. Black blood streamed down his face. The digital retouchers made sure he hadn’t aged a day. Across the bottom it read:

FINAL FIVE CONCERTS MAY 30–JUNE 8, LA, LV, SF

Kris stared up at the Blind King, and her guts turned to water. He was vivid. He was legion. Made up of lawyers and accountants and session musicians and songwriters, a colossus that could be seen from space. In contrast, she was puny and small, and stood in the empty lobby of the Best Western, seeing herself reflected in the glass doors, a shadow in navy slacks, nametag pinned to her vest, smiling at people as they ground out their hate on the ashtray of her face.

In the dark storeroom at the back of her brain, the overloaded racks tipped forward and the packages slid to the edge of their shelves, and she scrambled to push them back up. Her hands started to shake, and the world lurched and spun around her, and then Kris stood on the gas, and hauled ass, desperate to get to the toilet before she threw up, yanking her dad’s Grand Marquis onto Bovino Street, taking a right at Jamal’s Sunshine Market, plowing through the Saint Street Swamp.

Back here, abandoned houses vomited green vines all over themselves. Yards gnawed away at the sidewalks. Raccoons slept in collapsed basements and generations of possums bred in unoccupied master bedrooms. Closer to Bovino, Hispanic families were moving into the old two-story row homes and hanging Puerto Rican flags in their windows, but farther in they called it the Saint Street Swamp because if you were in this deep, you were never getting out. The only people living on St. Nestor and St. Kirill were either too old to move, or Kris.

She slammed into park in front of the house where she grew up and ran up the brick porch jammed onto the sagging facade, put her key in the lock, banged the water-warped door open with one hip, and bit her tongue to keep herself from calling out, “I’m home.”

Buy your mom a house. That was the rock-star dream. Kris had been so proud the day she’d signed the paperwork. Hadn’t even looked at it, just scrawled her signature across the bottom, never thinking one day she’d wind up living back here. She ran down the same front hall where her nineteen-year-old self had once stormed out, soft case in one hand, screaming at her mom and dad that just because they were scared of the world she didn’t have to be. Then Kris slammed open the fridge door and let the cool air dry her sweat.

She uncapped a green bottle with a brisk hiss. She needed to slow down for a second. The billboard had her too jacked up. She wanted to go online and get details, but she knew the most important thing already: the Blind King was back.

Excerpted from We Sold Our Souls: A Novel by Grady Hendrix. Reprinted with permission from Quirk Books.

Photograph by Marcus Obal.